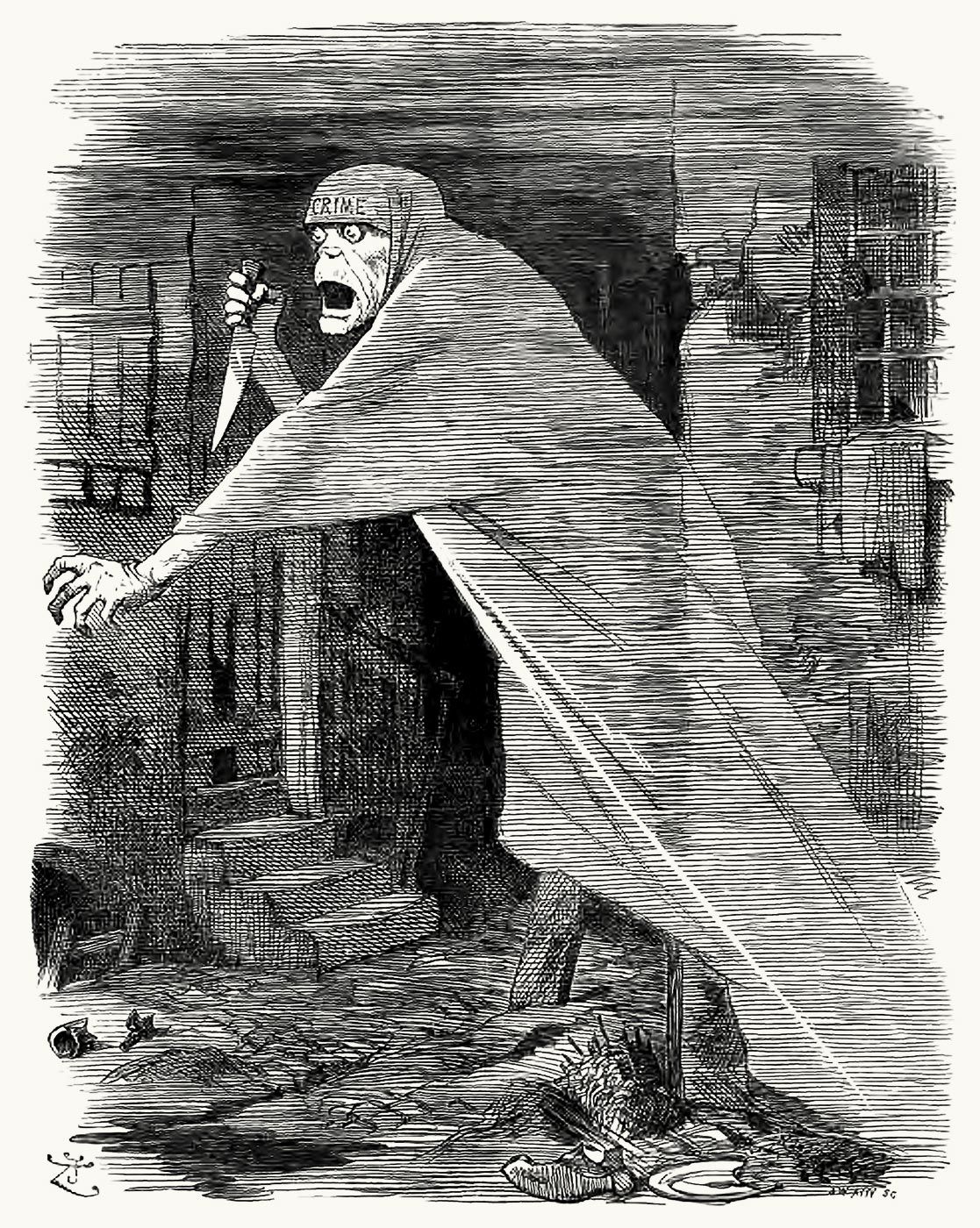

On 29 September 1888, readers of the satirical magazine Punch were confronted with an image that captured the anxieties of Victorian London. Entitled “The Nemesis of Neglect”, the cartoon depicted a gaunt, hollow-eyed phantom drifting through the narrow alleys of the East End. Cloaked and knife in hand, its forehead bore a single damning word: CRIME.

The message was stark. Jack the Ripper, or whoever was responsible for the Whitechapel murders, was not merely an isolated killer. He was the inevitable offspring of poverty, overcrowding, and decades of social neglect.

A Spectre in the Slums

The illustration was created by Sir John Tenniel, one of the most celebrated Victorian illustrators, better known today for bringing Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to life. For over fifty years Tenniel’s weekly contributions to Punch skewered the politics and social problems of the age. In 1893, he became the first cartoonist ever to be knighted.

But in September 1888, Tenniel turned his eye on the East End. His phantom figure, haunting and spectral, personified the fears of a city in shock after the murders of Mary Ann Nichols and Annie Chapman. It gave form to an idea gaining ground at the time: that London’s neglect of its poorest districts had produced conditions where such horrors were bound to happen.

Osborne’s Stinging Warning

The inspiration for the cartoon came from a letter to The Times on 18 September 1888. Its author, the Reverend Sidney Godolphin Osborne, signed simply “SGO,” was a well-known clergyman and social reformer.

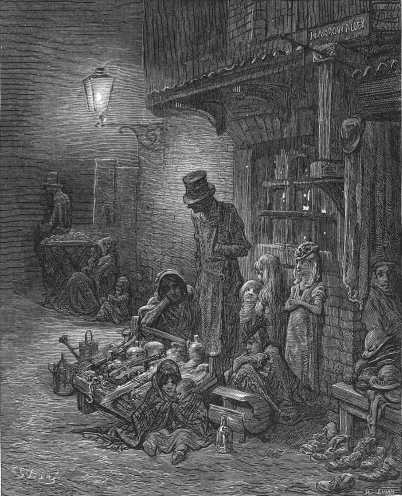

Osborne’s words were unflinching. He condemned the comfortable classes of the West End for allowing, within walking distance of their mansions, what he described as “a species of human sewage” that was “begotten and reared in an atmosphere of godless brutality.”

He argued that the Whitechapel murders were not unthinkable aberrations, but rather the grim harvest of misery, overcrowding, vice, and drunkenness in the slums. As long as London tolerated such conditions—dark alleys lit by gin shops, foul lodging houses, and families living in filth—such crimes, he warned, would continue to erupt.

A Poem and a Message

When Punch published Tenniel’s illustration, it accompanied it with a melodramatic verse that echoed Osborne’s point:

There floats a phantom on the slum’s foul air,

Shaping, to eyes which have the gift of seeing,

Into the Spectre of that loathly lair.

Face it—for vain is fleeing!

Red-handed, ruthless, furtive, unerect,

‘Tis murderous Crime—the Nemesis of Neglect!

The language may sound theatrical to modern ears, but the warning was deadly serious. Crime, the cartoon insisted, was not simply the work of one madman—it was the direct consequence of indifference to the suffering of the poor.

Still Relevant Today

More than 135 years later, “The Nemesis of Neglect” remains one of the most striking visual legacies of the Ripper era. It freezes in time the Victorian recognition—however belated—that the East End’s horrors were not confined to shadowy figures in the night, but rooted in social injustice.

The phantom Tenniel drew still drifts across history, reminding us that when societies ignore their most vulnerable, they may one day face consequences they can neither control nor escape.