On November 13, 1887, an event that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” unfolded at Trafalgar Square, casting a stark light on the social and political unrest gripping Victorian London. This violent confrontation was a direct response to long-simmering frustrations among the working class, fueled by economic disparity and political suppression. To truly understand its significance, one must delve into the events that set the stage for that fateful day, as well as the repercussions that would shape London’s turbulent history.

Seeds of Unrest: The Precursor to November 1887

The roots of Bloody Sunday trace back to February 8, 1886, when a protest of 5,000 unemployed laborers descended into chaos. After attending rallies organized by the London United Workmen’s Committee and the Social Democratic Federation, the crowd surged into the West End, shattering windows and looting shops along Oxford Street. American journalist George Smalley later described how, for three hours, the mob was “‘in absolute possession and unchecked control of the West End of London.”1 This incident led to the resignation of Commissioner Edmund Henderson and the appointment of Sir Charles Warren, whose strict military discipline would define his tenure.

Rising Tensions and the Struggles of the Working Class

The 1886 riots exposed deep-seated class tensions in London. Howard Goldsmid, a journalist of the era, remarked that many rioters, though branded as looters, were driven by a righteous anger against the system, an attempt to voice their frustrations against “harsh, bloated, and unsympathetic capital.”2 However, no substantial reforms were enacted to alleviate these grievances. By 1887, London’s economy had further deteriorated, leaving 20,000 men unemployed, with districts like East London, Battersea, and Deptford bearing the brunt of joblessness. Trafalgar Square had become a haven for political agitation and informal gatherings, a situation that alarmed Warren.

The Prelude to London’s Unrest

By the summer of 1887, Warren, increasingly worried about Trafalgar Square’s potential to incite broader unrest, appealed to Home Secretary Henry Matthews to ban public assemblies there. Initially hesitant, Matthews eventually conceded in November, empowering Warren to impose a ban. The prohibition spurred immediate resistance from leftist groups. The Metropolitan Radical Association organized a massive demonstration for November 13, advocating for Irish nationalist causes and demanding the release of imprisoned Irish MP William O’Brien.

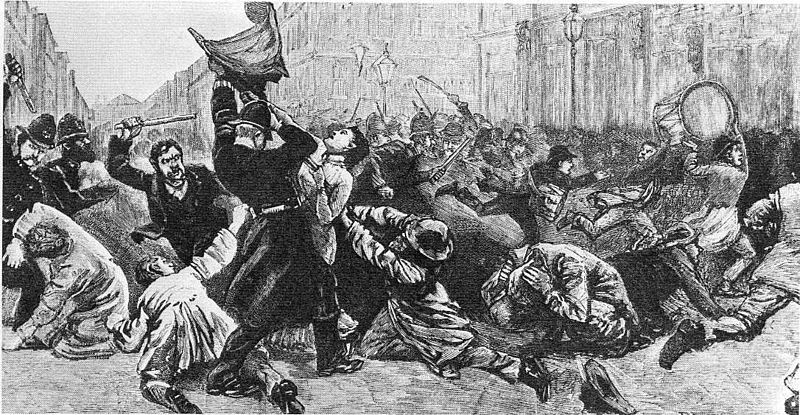

The Day of Reckoning: November 13, 1887

The protest drew an estimated 10,000 to 150,000 demonstrators, facing 2,000 police officers and 400 soldiers. The police adopted an aggressive stance, forcibly dispersing the crowd. Eyewitness accounts painted a vivid picture of the chaos: Edward Carpenter, a socialist poet, described the relentless police charge, saying, “The order had gone forth that we were to be kept moving… riding roughshod in all directions, scattering, frightening, and batoning the people.”3 Walter Crane, an artist present at the scene, likened the violence to warfare: “I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life – only the attack was all on one side.”4

The result was brutal: 200 injuries, broken bones, and nearly 300 arrests. Notable socialist figures like John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham were apprehended, solidifying their status as working-class champions. Annie Besant, another prominent activist, detailed the violence, recounting the bloodied faces and battered bodies of workers who dared to protest: The “peaceable law-abiding workmen, who had never dreamed of rioting, were left with broken legs, broken arms, and wounds of every description.”5

The Aftermath and Its Martyrs

Among those gravely affected was William Bate Curner, a stonemason who succumbed to head injuries a month after the protest. His widow maintained that he was essentially killed by police brutality, a claim that resonated with many sympathizers. His funeral, though small, featured notable figures like Annie Besant and W.T. Stead, with the socialist choir performing William Morris’ “Death Song.” The conservative Morning Post, however, disputed these allegations, arguing that Curner died of natural causes and criticizing the liberal press for what it saw as propaganda:

“The champions of lawlessness were sorely in need of a martyr or two, whose death might be effectively [used] as advertisements of their cause. The result of the inquiry is eminently satisfactory in so far as it may lead some well-meaning but injudicious persons to look with more suspicion upon the other stories of massacre and brutality and the like, which are dressed up in such specious garb to harrow their feelings.“6

Continued Resistance and Calls for Reform

Bloody Sunday did not silence dissent. Protests persisted into 1888, epitomizing the unyielding spirit of the movement. Public rallies celebrated the release of Burns and Cunninghame Graham in February 1888, marked by calls for Warren’s resignation. Steward Headlam, a vocal critic, provocatively stated that even Jesus Christ would have been arrested under Warren’s strict regime.

Legacy and the Road to Whitechapel

The legacy of Bloody Sunday was profound, setting the stage for a continued struggle between London’s working class and the authorities. It marred Warren’s image, painting him as an autocratic figure. This friction between the public and the establishment would only deepen as London approached 1888, a year that would usher in a different kind of terror with the infamous Whitechapel murders.

Sources

Besant, A., An Autobiography (1939).

Goldsmid, H.J.J., Dottings of a Dosser (1886).

Jones, Richard (2018): The London of Jack the Ripper.

Morning Post (Newspaper).

Smalley, G., London Letters (1890).

Stubley, Peter (2012): 1888. London Murders in the Year of the Ripper. The History Press.

Title photo: “Bloody Sunday” from “The Illustrated London News” (Source: Wikimedia Commons)